Sing Street

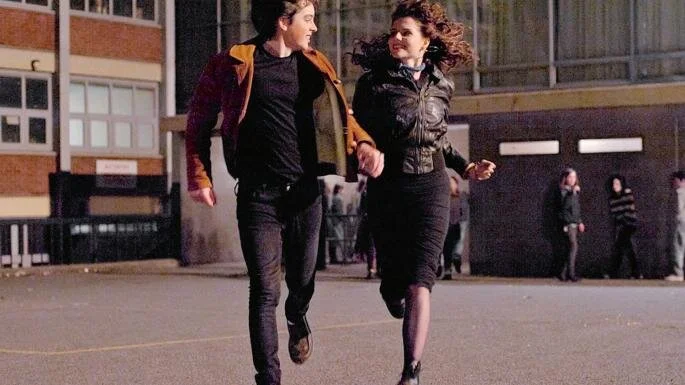

In between days: Ferdia Walsh-Peelo and Lucy Boynton as the lovers in Sing Street. Snap Stills/Rex/Shutterstock

John Carney’s latest musical feature is a highly entertaining romp through the 1980s, with great performances from its young cast, and the director displaying the sure hand of a mature filmmaker approaching the height of his powers.

Conor, 15, is taken out of his posh Jesuit school when his parents hit hard times, and sent to the local Christian Brothers on Synge Street. It’s a rough establishment, and he immediately attracts the attentions of resident schoolyard bully Barry (Ian Kenny) and staffroom bully Brother Baxter (Don Wycherley). He is drawn to a pretty older girl Raphina, 16, played by Lucy Boynton styled to look like Pat Benatar circa 1983, who hangs around posing as a model on the steps opposite the school. He tries to impress her by claiming to be a singer, and then has to speedily recruit a band.

Ferdia Walsh Peelo is completely delightful in the lead, while his raggy bunch of band misfits are all perfectly observed. Ben Carolan does a hilarious job as producer Darren, and Mark McKenna is the rabbit-loving musical prodigy Eamon. They recruit a black keyboard player, a cool Percy Chamburuka as Ngig, who conjures up the ghost of Phil Lynott.

Maria Doyle Kennedy plays the mother, a casting decision which nods to her role as a glamorous singer in Alan Parker’s The Commitments, this film’s obvious precursor. Then cast as a glamour puss, and now the mum, the casting of Doyle Kennedy will offer a poignant reflection for the forty-five plus demographic.

Conor’s older brother, the college drop-out Brendan (Jack Reynor), becomes his musical mentor. A credit dedication “for brothers everywhere” underlines the importance of this story strand. This material had the potential to allow an exploration of the malaise and problems of this era, but though the scenes are beautifully played by Reynor, they lack real heft. Brendan “I used to be a jet engine” has clearly not made the most of his talents, but the relentless upbeat tempo of the film means you never really fear for him.

There is plenty of Eighties colour in the brilliant costumes by Tiziana Corvisieri. They’re all New Romantics, with a light sprinkling of Village People and The Cure. There are classic songs from Duran Duran, Hall & Oates and Spandau Ballet, while a number of new songs are such clever pastiches of 80s bands you will be certain you know them, in particular the catchy Drive It Like You Stole It. The virtuosity of the music and its deployment in the story is a triumph. The credit goes to Carney himself and veteran Eighties pop composer Gary Clark, of Mary’s Prayer fame. There is a fine Glen Hansard ballad towards the end.

We get plenty of the pizzazz of the Eighties, but less of the dark side. Raphina shows definite signs of learned victimhood, and there are some murky hints about her family background. Similarly, Conor is invited to use Brother Baxter’s private bathroom to wash off his make-up. The line “You’re pretty enough without make-up” prompts him to scarper, though he later makes reference to “rapists and bullies”. There is an implicit understanding of the levels of clerical and familial abuse that have been recently uncovered from this period, but characters and filmmaker don’t want to go there in any detail, or not enough to drag down the happy vibe.

Back to the Future, the iconic film touchstone of the period, is a key reference, including a fantasy scene in which a gawky video shoot with badly dressed and badly dancing teenage girls magically transforms into a sparkling 1950s American prom night. Carney is like a filmmaking Marty McFly, time travelling with his camera three decades into the past and correcting everything that was wrong with Ireland in the Eighties. He takes revenge on the terrible Christian Brother; creates a band that actually sounds like a professional group; and confidently romances the most beautiful girl. There is more than a hint of rose-tint here.

This lightness of touch is both the film’s core strength but also contributes to its ultimate flaw. The plotline involving Barry lays on the sugar coating too thickly. The relentless upbeat rhythm and stripping out of the dark side of the 1980s has a downside. In terms of storytelling, music and performances, this film should be getting five stars, but the accumulated positivity leaves a mild sense of dissatisfaction. The Eighties were much more suffocating than this.

Irish film has traditionally been criticised for being too angsty and miserabilist. Too much rain falling and people getting into a state about everything. Several of the current generation of filmmakers are drawn to a traumatic core, but with a much glossier feel. Think Room or Calvary, for example. Carney’s film and its jubilant tone belongs to a more upbeat strand in recent Irish cinema. Feel-good films are hugely enjoyable and often extremely good; they are less often truly great.

Sing Street

12A 106 mins

★★★★